By Rachel Wells Hall

The melody sung to John Newton’s 1779 hymn “Amazing grace, how sweet the sound” is, without a doubt, America’s best-loved hymn tune [1]. Unlike Lowell Mason’s “Nearer, my God, to thee,” the “Amazing grace” tune is of unknown origin. It first appeared in print in 1829 without any composer attribution, and there were thought to be no earlier surviving instances of the tune. However, an 1828 manuscript by Lucius Chapin (1760-1842), who was famous in his day as a hymn tune writer, raises the possibility that Lucius was its composer.

Lucius and his brother Amzi (1768-1835) were among the first and most influential composers to harmonize American folk hymns, using principles they had absorbed from New England and English church music, and perhaps from the oral tradition as well. They also composed hymns in a similar style. The brothers came from a large, musical Massachusetts family. Their mother was an exceptional singer, though she did not read music, and two of their brothers also became singing masters. Lucius and Amzi moved south and west as young men and taught singing schools throughout their lives. In 1828, Lucius was living in central Kentucky and Amzi in western Pennsylvania [2].

The 1828 manuscript was mentioned in passing in James Scholten’s 1972 dissertation on Lucius and Amzi Chapin. Scholten provided few details and seemed unaware of its significance. In page 87, Scholten wrote of Lucius’ son Cephas (1804-1828),

On July 25, 1828, [Cephas] died from typhus in Oxford, Ohio en route home to visit his parents. There are three tender expressions of paternal love and grief on the back of Cephas’ last letter penned there by Lucius, the tunes AMAZING GRACE and BRAINARD and a brief poem [2].

The familiar melody had a number of titles in its early publications: ST. MARY’S, GALLAHER, HARMONY GROVE (Shenandoah Harmony, p. 300), NEW BRITAIN (Sacred Harp, p. 45), and more. The one title it did not have was AMAZING GRACE, though that title was used for at least two other melodies. The tune wasn’t paired with Newton’s text until 1835. I was curious to see the manuscript, because neither John Newton’s hymn “Amazing grace, how sweet the sound” nor any of the tunes known for that text are associated with the Chapin family by modern scholars. However, the great nineteenth-century scholar W.E. Chute (1832-1900) attributed the melody to the Chapins, though his evidence is unknown.

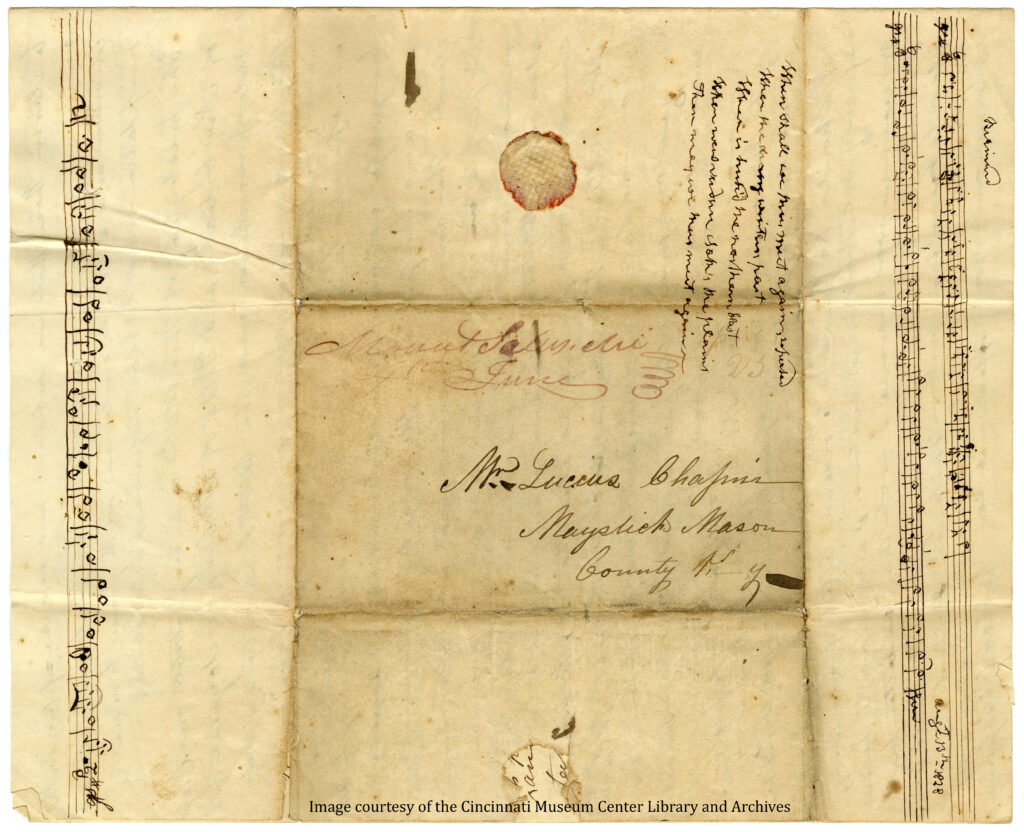

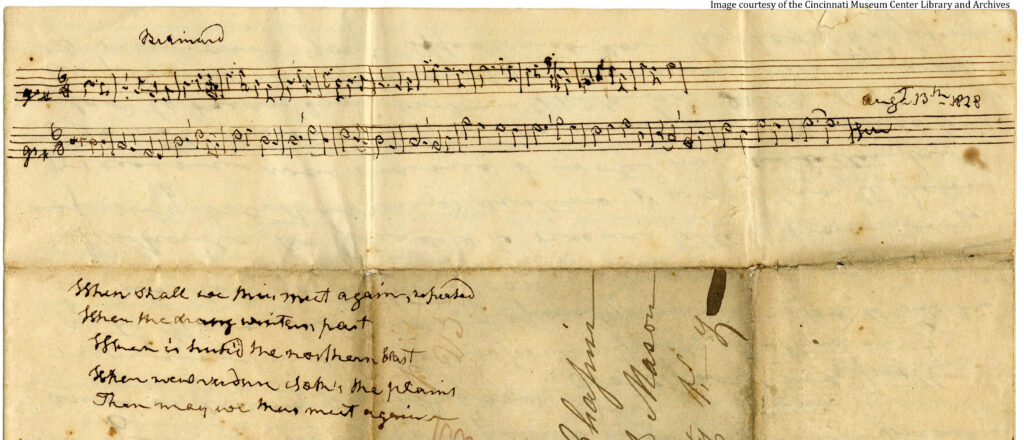

I contacted Christine Engels of the Cincinnati Museum Center Library and Archives and she sent me a copy of the back of Cephas’ letter, reproduced here with permission. You can click on the image to see more detail. The date August 13, 1828 is visible in the lower right corner.

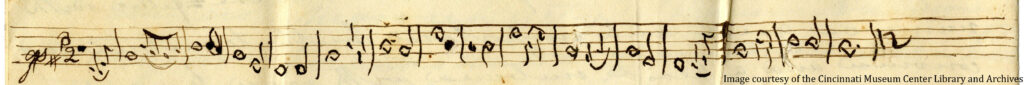

Since Lucius doesn’t name the tune on the left, I’m going to call it NEW BRITAIN, which is its most common name (hymn tune titles are traditionally written in capital letters). Here’s a closeup. Despite teaching shape notes for decades, Lucius never adopted them in his personal manuscripts.

It is possible that NEW BRITAIN was added to the manuscript after 1828, or copied from a source that does not survive. However, the version here doesn’t exactly match any tune found, either published or in manuscript, in Nikos Pappas’ exhaustive index of over 60,000 early American hymn tunes (1700-1870) [3]. It is closest to the tune ST. MARY’S found in Shaw and Spilman’s Columbian Harmony (1829) [4]. Like Lucius, Shaw and Spilman lived in central Kentucky. More about that later.

Should we attribute the NEW BRITAIN tune to Lucius? Probably not. It is possible he composed it, but this isn’t like finding a Beethoven sonata written in Mozart’s handwriting, or even like finding NEW BRITAIN in Lowell Mason’s handwriting. Even if Lucius were the first to notate the tune, the concept of “authorship” in this repertoire is difficult. Composers felt free to write arrangements of popular sacred or secular melodies in oral tradition and publish them, either as unattributed tunes or with their own names attached. They also made their own versions of tunes in books or manuscripts, appropriated and rearranged European classical music, and composed music from scratch in a folk idiom [5].

Authorship as regards the Chapins is particularly difficult to pin down. The three most popular American folk hymns, TWENTY-FOURTH, NINETY-THIRD, and ROCKBRIDGE, are all ascribed to Amzi or Lucius (see The Sacred Harp, pages 47 and 31, and The Shenandoah Harmony, page 1, respectively) [3]. The brothers never published books, and the manuscripts that survive don’t clarify the situation. Lucius and Amzi most probably composed harmony parts, but we don’t know to what extent they “wrote” the tunes.

The other tune on Cephas’ letter, BRAINARD, gives some tantalizing clues to Lucius’ musical process. It is a folk hymn most often called INDIAN’S FAREWELL or PARTING FRIENDS (see page 271 of The Shenandoah Harmony). In this case, there are several published versions prior to 1828, though none match Lucius’ tune exactly [3]. What’s interesting here is the fact that Lucius appears to be making a transcription. He writes the tune twice, using two different rhythms and time signatures. He mistakenly writes “6/8” as the time signature for both versions, and the first version has an incomplete measure. In all the published sources, the first note is on the downbeat, not a pickup, as it is here. After viewing the letter in person, I believe that Lucius was also transcribing NEW BRITAIN, as there are scrape marks where he corrected mistakes.”

Why did Lucius write these particular tunes on the letter, presumably thinking of his son? INDIAN’S FAREWELL was usually coupled with the text “When shall we all meet again” by Anna Jane Vardill (1807). (Although Vardill wrote the poem in the persona of “Casmerian” (Kashmiri) Indian, it was spuriously associated with both Native Americans and missionaries, and perhaps Lucius’ title refers to David Brainerd, a well known missionary to the Indians.) Lucius writes a different text, however—one more tender, and one associated with the death of a child:

When shall we thus meet again (repeated)

When the dreary winter’s past,

When is hushed the northern blast,

When new verdure clothes the plain,

Then may we thus meet again.

This entire poem appears in Daniel Huntington’s 1838 memoir of his daughter Mary, who died in 1820 at the age of six. On page 43, Huntington writes that he composed the poem for her Sunday school class in 1819. It was published in the newspaper Boston Recorder in that year and somehow it made its way into Lucius’ hands. (If the beginnings of Vardill and Huntington’s texts seem familiar, it’s because they were inspired by the opening lines of Macbeth.)

What text or texts might Lucius have associated with NEW BRITAIN? Texts and tunes usually had an independent existence in this period. The two texts used in Columbian Harmony (1829) are Charles Wesley’s “Come, let us join our friends above” and Isaac Watts’ “Arise my soul, my joyful pow’rs.” Of those two, “Come, let us join” is closest thematically to “When shall we thus meet again.” It is one that Sacred Harp singers today associate with memorials, though we sing a different tune, ARNOLD, to these words:

Come, let us join our friends above,

That have obtain’d the prize;

And on the eagle’s wings of love,

To joy celestial rise.

If Lucius didn’t compose NEW BRITAIN, then who did? The basic structure of the tune is ancient. NEW BRITAIN is a folk hymn—a sacred melody that existed, in some form, in oral tradition prior to being notated. It belongs to a recognized “tune family,” or group of tunes, sacred or secular, that share enough structure and melodic phrases that they seem to be descended from a common root. Other related tunes include Amzi Chapin’s TWENTY-FOURTH (written in the 1790s) and, more distantly, the African-American spiritual “Swing low, sweet chariot” (published in 1873, but definitely older). The folk hymn CONSOLATION (attributed to the Chapins when first published in 1812) has the same contour, but is in the minor mode. Though clearly different melodies, all four tunes share the same four-phrase structure, with first phrase ending on the fifth below the tonic, the second phrase ascending to the fifth above, the third phrase descending from there down an octave, and the final phrase ascending to the third before returning to the tonic. All four of these tunes remain in print in multiple modern hymnals.

However, just because a tune is a folk hymn doesn’t mean that there wasn’t an originator for a particular variant of the tune family. There were at least ten slightly different versions of NEW BRITAIN written down from 1828 to 1840 in Kentucky, Virginia, Tennessee, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina [3]. Three of these were from central Kentucky. This argues for oral transmission, but the fact that each version differs from the others only in the amount of ornamentation notated suggests that one person, perhaps an itinerant preacher or singing master, was the “vector” that spread the tune through this area in the late 1820s to 1830s.

I mentioned at the beginning of this post that Lucius’ version was closest to ST. MARY’S in Shaw and Spilman’s 1829 Columbian Harmony. There may have been a closer connection between Charles Spilman, Benjamin Shaw, and Cephas Chapin. Charles and Cephas were born within a year of each other and both were Presbyterians. In 1828, Charles and Benjamin were at Centre College in Danville, about 90 miles from the Chapin family. Though Cephas was in Alabama prior to his death, he had previously been teaching singing school in Kentucky and stated in a letter that he had entered Centre College, although he didn’t graduate. Cephas’ letters say he participated in a revival there in 1826. Did Charles and Benjamin learn the tune from Cephas? Or vice versa? Or was this tune commonly known at Centre College?

This possible connection raises the question of whether Lucius (or Cephas) wrote the arrangement of ST. MARY’S in Columbian Harmony. There are some aspects of the harmony—the four-part setting, and the variety of chords—that are found in the Chapin arrangements. However, the static treble (top line) and bass, the narrow, high range of the treble in relation to the melody (tenor), the use of parallel thirds, and the dominant seventh chord before the final note all argue against Lucius as arranger. As for Cephas, we have no record that he composed or arranged music.

What, if anything, does this manuscript add to the story of “Amazing Grace”? It’s fascinating that there is a direct connection between America’s best-loved hymn tune and our “first family” of sacred folk song. I could speculate endlessly on where Lucius learned the melody, or whether he composed this variant of the tune family. However, the one thing certain is that he wrote the tune on the back of the last letter he ever received from his son. The tune must have had emotional significance for him, and perhaps provided some consolation. In that, he would not be alone.

POSTSCRIPT: THE CHAPINS AND THE ANTISLAVERY MOVEMENT

Another interesting story, though tangential, is the Chapin family’s connection to the antislavery movement. If you’ve read the story of John Newton (the author of the words to “Amazing Grace”) or seen the Broadway play, you’ll know that he was the captain of a slave ship who later rejected his past and advocated against slavery. The Chapin family lived in central Kentucky and some of their neighbors owned slaves, though there weren’t large plantations in the area. However, the diary of Cephas’ sister Harriet survives, and she was profoundly antislavery, though as a woman she didn’t have power to make decisions about her household. She thanks God that her father is “an Emancipator.” I don’t know if that means that he had slaves and set them free or if he didn’t believe in slavery and never owned slaves (I think the latter). Harriet considered it her duty to educate the two young African-Americans who worked for the family, an act that would have been illegal in many states. Harriet died in 1827, just a year before Cephas—a fact that must have made Cephas’ death even more difficult for their parents.

In general, the early revivals in Kentucky were far more democratic than were churches later in the 19th century. Both white women and African-Americans—even slaves—were called on to testify and even preach, and everyone participated in group singing, which was one of the hallmarks of these revivals. So the fact that this particular tune, whoever wrote it, is often associated with black spirituals and related to “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” is not surprising, as it was first popular in a mixed environment.

POSTSCRIPT: CEPHAS’ DEATH

I found a poem about Cephas’ death and obituary online.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Christine Engels of the Cincinnati Museum Center Library and Archives for her assistance in locating the Chapin letter, the Museum Center for permission to post images, and Nikos Pappas for his willingness to share his invaluable research in documenting American sacred music.

REFERENCES

[1] Steve Turner, Amazing Grace: The Story of America’s Most Beloved Song (New York: Harper Collins, 2002).

[2] James Scholten, “The Chapins; a study of men and sacred music west of the Alleghenies, 1795-1842” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1972).

[3] Nikos Pappas, Southern and Western American Sacred Music and Influential Sources (1700-1870). Database, 2015.

[4] Benjamin Shaw and Charles H. Spilman, Columbian Harmony, or, Pilgrim’s Musical Companion (Cincinnati: Lodge, L’Hommedieu & Hammond, 1829).

[5] Nikos Pappas, “Patterns in the Sacred Music Culture of the American South and West (1700-1820)” (PhD diss., University of Kentucky, 2013).